Drug overdose deaths spiked almost 22 percent in New Jersey last year, the state Medical Examiner’s Office reported Wednesday, largely due to opioids including heroin and fentanyl.

Heroin Crisis

-

Puerto Rico is dumping off its heroin addicts in Philly

-

Fairhill's 'El Campamento,' where drugs make the rules

-

Newall: When will someone clean up Philly's heroin camp?

-

Parents of beloved but troubled Philly Twitter user speak

-

Inquirer Editorial: Pipeline from Puerto Rico adds new dimension to Philadelphia's heroin crisis

The finding is almost identical to the 23 percent increase in deaths in Pennsylvania that the local division of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration reported several months ago.

In some ways, however, the latest data are even more disturbing: While Pennsylvania overdoses have been rising annually for more than a decade, and now far exceed the national average, in New Jersey they had held steady for a couple of years and even seemed to be declining slightly. National data are not available yet, but a number of other states had also experienced plateaus in drug deaths that turned out to be temporary.

And while the opioid crisis clearly has caught the attention of officials at all levels of government —Philadelphia City Council is expected to vote Thursday on a series of recommendations aimed at reducing deaths — solutions have proven elusive.

"I know that 2016 is going to substantially exceed 2015," said Gary Tennis, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs.

The prescribing of opioid painkillers like Percocet and OxyContin, which can lead some patients to become addicted and turn to far cheaper heroin, still has not been brought under control, he said, and treatment programs are vastly underfunded. Addiction is rising, not falling, he said.

Meanwhile, some of "the drugs that are being circulated are extraordinarily powerful, far more than the users are expecting," Tennis said.

A batch of heroin sold in Philadelphia over the weekend is suspected of causing nine overdose deaths in 36 hours in Philadelphia. Less than three weeks earlier, police reported, several dozen people overdosed in the city in an 18-hour period, but most survived. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid often added to heroin to make the product more profitable, is believed to have played a role in many of those cases, as it has in surges in deaths around the country in recent months.

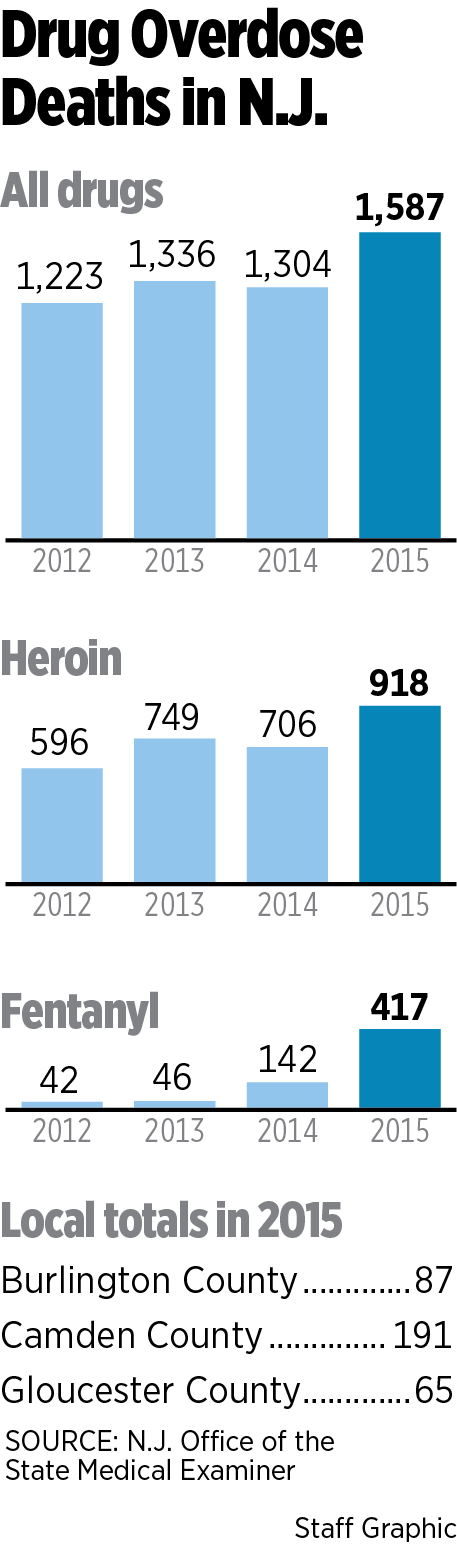

The New Jersey Office of the State Medical Examiner said Wednesday that there were 1,587 drug-related deaths last year compared with 1,304 in 2014. Multiple drugs are often identified in toxicology reports, but increases in two of them stood out: Heroin was identified in 918 victims, a 30 percent increase over the previous year. And 417 deaths involved fentanyl, triple the number in 2014.

The New Jersey Office of the State Medical Examiner said Wednesday that there were 1,587 drug-related deaths last year compared with 1,304 in 2014. Multiple drugs are often identified in toxicology reports, but increases in two of them stood out: Heroin was identified in 918 victims, a 30 percent increase over the previous year. And 417 deaths involved fentanyl, triple the number in 2014.

Even counties like Camden and Ocean that have aggressively pursued prevention strategies such as equipping police with the overdose-reversal medication naloxone experienced significant rises in drug deaths, suggesting that there could have been even more fatalities. Camden County police reported reversing 115 overdoses last year in the city of Camden alone, yet deaths were up 38 percent, to 191.

Despite the increases, New Jersey’s drug fatality rate is likely to remain below the national average in the yet-to-be-released federal data.

The DEA’s Philadelphia Division reported in July that there were 3,383 drug-related deaths in Pennsylvania last year, based on data from county coroners. Fentanyl was up 93 percent, the DEA said.

There were 720 drug-related deaths in Philadelphia in 2015. The city already is well beyond that this year, with some projecting 900 fatalities by the end of the year.

Last weekend's surge of overdoses in the Kensington area, a major drug market that also draws buyers from the suburbs, has not shown up in nearby counties in either state, spokesmen for several of them said.

But the underlying reasons behind rising fatalities are even more dangerous, said Louis E. Baxter, a physician and addiction consultant to the state of New Jersey.

Even as more people have become addicted to prescription painkillers, he said, heroin has become an easier substitute because it is now so pure that it can be smoked and snorted. Needles were a far scarier proposition, particularly for the middle class rural and suburban residents who are at the leading edge of the overdose epidemic.

But "the problem is primarily access to treatment," he said. "Many people that require treatment do not get it," he said, and many insurance companies won't cover physician office visits for the medications that can prevent relapse.

For that reason, Baxter said, patients in his own addiction treatment practice in Blackwood generally have to pay cash.

No comments :

Post a Comment